The 1,000-Year-Old Schism That Pope Francis Seeks To Heal

hide captionTourists walk past a poster of Pope Francis hanging on the Church of the Nativity in the West Bank town of Bethlehem on Monday. Pope Francis' trip to the Mideast later this week will commemorate the 50th anniversary of a historic rapprochement between Catholics and Orthodox, who split nearly 1,000 years ago.

Tourists walk past a poster of Pope Francis hanging on the Church of the Nativity in the West Bank town of Bethlehem on Monday. Pope Francis' trip to the Mideast later this week will commemorate the 50th anniversary of a historic rapprochement between Catholics and Orthodox, who split nearly 1,000 years ago.

Mussa Qawasma/Reuters/LandovBut the official purpose of the visit is to commemorate the 50th anniversary of a historic rapprochement between Catholics and Orthodox and to try to restore Christian unity after nearly 1,000 years of estrangement.

Meeting in Jerusalem in 1964, Pope Paul VI and Orthodox Patriarch Athenagoras set a milestone: They started the process of healing the schism between Eastern and Western Christianity of the year 1054.

Moves toward closer understanding followed, but differences remain on issues such as married clergy and the centralized power of the Vatican.

It was the current Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, Bartholomew I — known as the "first among equals in the Orthodox church" — who asked Francis to join him in Jerusalem.

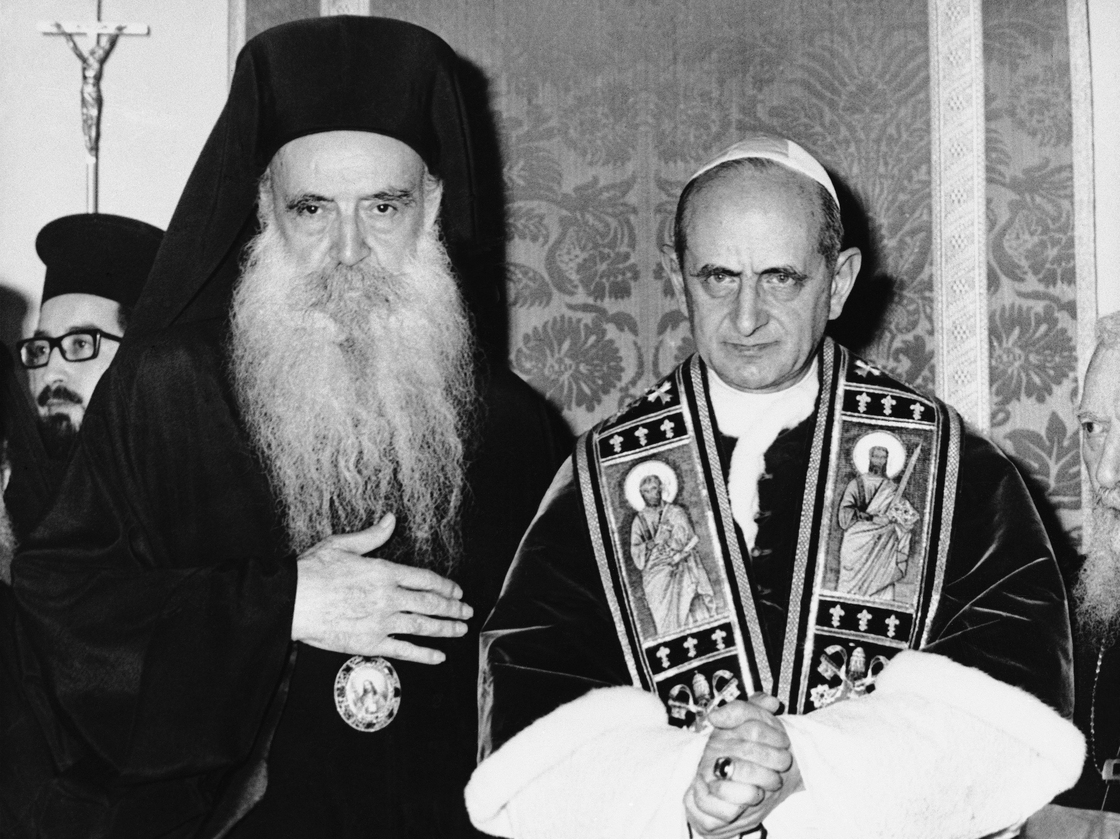

hide captionPope Paul VI of the Roman Catholic Church and bearded Orthodox Patriarch Athenagoras of Constantinople pose during a historic meeting on Jan. 8, 1964, on the Mount of Olives in a part of Jerusalem that was controlled by Jordan at the time. It was the first meeting between leaders of the split church since the East-West Schism of 1054.

Pope Paul VI of the Roman Catholic Church and bearded Orthodox Patriarch Athenagoras of Constantinople pose during a historic meeting on Jan. 8, 1964, on the Mount of Olives in a part of Jerusalem that was controlled by Jordan at the time. It was the first meeting between leaders of the split church since the East-West Schism of 1054.

AP"He talks about presiding in charity. Wow!" Mickens says. "When he says things like this, rather than having the power over other churches, this is music to ears of Orthodox and other separated brothers and sisters in the faith because they want a pope, a leader, but not with all the power of that the Bishop of Rome has accrued over the centuries."

Perhaps nowhere in the world are the animosities between rival Christians more palpable than at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem's Old City.

In that holy site, Christian denominations pray separately and each jealously lays claim to overseeing the location where Jesus was buried and resurrected.

It's there that the leaders of the Catholic and Orthodox churches will hold what Vatican spokesman the Rev. Federico Lombardi describes as an unprecedented ceremony.

"This is the key moment of the papal trip — a joint public prayer of all Christian communities in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the central site of our faith," he says. "It has never happened before. This is extraordinarily historic.

John Allen, The Boston Globe's Vatican analyst, says "this will be a very warm, fraternal encounter full of very positive symbolism and generating hope about putting Humpty Dumpty [the split Christian church] back together again."

Allen points out that although Bartholomew in Constantinople is the "first among equals," the real Orthodox power lies with the much bigger Russian Orthodox Church.

Based in Moscow, the Russian hierarchy fears Christian unity means submission to the Vatican, which it accuses of poaching on its turf.

"They accuse the Vatican of promoting proselytism in Russia that is seeking to make converts in Russia," says Allen. "Until those problems are solved there isn't any realistic hope for real Christian unity right now. The substance of the relationship between the Vatican and the Orthodox world is not located in Constantinople. It has to be worked out in Moscow."

hide captionPope Francis meets Bartholomew I, the first ecumenical patriarch to attend the installation of a pope since 1054, at the Vatican on March 20, 2013.

Pope Francis meets Bartholomew I, the first ecumenical patriarch to attend the installation of a pope since 1054, at the Vatican on March 20, 2013.

L'Osservatore Romano/APIn the mid-20th century, Christians were 20 percent of the Middle East's population. Today, Allen says, the high estimate is 5 percent.

"Christians of course are in the firing line in many parts of the Middle East, Syria being the most recent example, but also in Egypt and other places," Allen says. "And so certainly the plight of persecuted Christians is something that is of deep concern to the church, and part of the agenda for visiting this part of the world is always to give a shot in the arm to what remains of the Christian footprint there."

Earlier this month, Pope Francis said that to honor the sacrifice of those who today are killed for their faith, Christians must renew their commitment to reconciliation and full Christian unity.

No comments:

Post a Comment