Why the Knights of Columbus?

For much of U.S. history, Columbus has symbolized civic unity and the hope of building an inclusive society

During the long summer of 2020, when scores of statues of Christopher Columbus have been vandalized or removed around the United States, it is important to remember why those statues were erected. How did Columbus come to be such an important figure in the popular imagination during most of the nation’s history?

Above all it had to do with the possibility of building in the Western hemisphere a new civilization — one that would bring together European traditions and ideas with the Native American peoples, traditions and the flora and fauna of the new continent. What remains striking, after more than five centuries, is the hopefulness of this venture, and the belief that there was an opportunity to create a better way of life that immigrants to, and within, the New World still share today.

The first members of the Knights of Columbus were influenced by this vision and also instrumental in promoting it. Just two years after the death of the Knights’ founder, Father Michael McGivney, councils enthusiastically participated in the first national Columbus Day, declared in 1892 for the quadricentennial of the great navigator’s landing. For them and many others, Columbus was celebrated as a figure of civic unity and a symbol that immigrants, particularly Catholics, possessed a rightful share in American identity.

THE ATTRACTION OF ‘COLUMBUS’

As early as the colonial period, the name “Columbia” was used as a figurative synonym for America. The poet Phillis Wheatley, an African American, wrote several striking poems in praise of Columbia during the Revolutionary War. After independence, the capital of the United States was sited in a district called Columbia, while artists represented Columbia as an allegorical female figure embodying the virtues and the hopes of a new civilization no longer bound to Europe.

It was especially after the Civil War, however, that Columbus soared in popularity. Much of this attraction can be explained by the explosion in sea traffic in the second half of the 1800s. The technological shift from sail to steam and the lower cost of travel opened the oceans to the masses on both sides of the Atlantic. As the first transoceanic seafarer, Columbus became a popular hero, and in the decades before and after 1900 he was admired in Europe almost as much as in the Americas. It was no coincidence that the many statues and monuments to him (Barcelona, Genoa, Buenos Aires, New York City) began to be built around that time.

It was also no coincidence that certain immigrant groups — Irish, Italians, Hispanics and other Catholics — that felt marginalized in a still WASP-dominated United States identified themselves with a universally admired historical figure who also happened to have been Italian, to have sailed for Spain, and to have brought Catholic Christianity to the Western Hemisphere. Columbus could be presented as legitimating their presence at a time when anti-Catholicism and anti-immigrant nativism were quite common. This, of course, was the atmosphere in which the Knights of Columbus was founded.

When Father McGivney, the son of Irish immigrants, proposed a name for the fraternal and charitable organization in 1882, his choice was “Sons of Columbus.” After debate with the founding members — all of them laymen, most of them Irish — the group finally settled upon “Knights of Columbus.”

While “Knights” invoked the chivalric orders, with their code of ethics, aspiration to virtue and defense of the most vulnerable, the adoption of Columbus as patron signified that Catholics had been in the New World from the beginning — that is, from the very day that it became “New.”

As founding member William Geary put it, the name conveyed that Catholics “were not aliens” in America but rather participated in the very foundation of this new civilization. With respect to American society at large, the choice of Columbus was a comfortable one, since it embraced an existing and very popular object of admiration.

CATHOLICS HAD BEEN IN THE NEW WORLD FROM THE BEGINNING — THAT IS, FROM THE VERY DAY THAT IT BECAME ‘NEW.’

CELEBRATING CIVIC UNITY

When President Benjamin Harrison first proclaimed Oct. 12, 1892, as Columbus Day, the idea — lost on present-day critics — was that the holiday would recognize both Native Americans, who were here before Columbus, and the many immigrants who were then coming to this country in astounding numbers. Like the Columbian Exposition dedicated in Chicago that year, it was to be about our land and all its people.

The 1892 Columbus Day parade in New York City was telling in this regard. Harrison had especially designated the schools as centers of the Columbus celebration, and thousands of public school students marched, followed by students from Catholic and other private schools, each wearing their respective uniforms. These included the Hebrew Orphan Asylum, the Dante Alighieri Italian College of Astoria and the Native American marching band from the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, which speaks volumes about the spirit of the original Columbus Day.

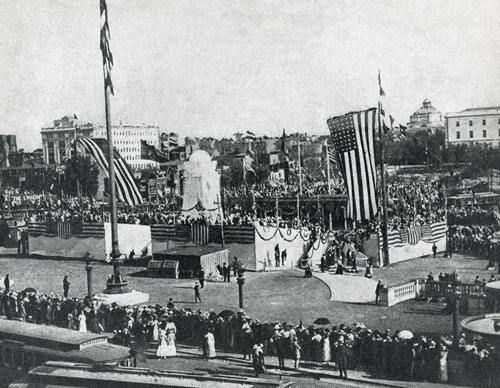

On the same day, 6,000 Knights of Columbus marched in a parade in New Haven, Conn., where a 600-voice choir, led by the choir director of St. Mary’s Church, performed a concert that included various national anthems. The event drew some 40,000 people, then the largest crowd in New Haven’s history.

In the years that followed, the Knights of Columbus encouraged Columbus Day celebrations around the country as well as monuments in Columbus’ honor.

In 1906, Colorado became the first state to declare Columbus Day an annual holiday, and within six years, the movement had taken on national proportions, with observances in 30 states.

The Ku Klux Klan was among the holiday’s strongest opponents, since it commemorated a man who was Catholic and a non-Anglo. Despite attempts to put an end to Columbus Day as a state holiday, it continued to be observed. Oct. 12 was established as a national celebration by annual presidential proclamation in 1934; it became a federal holiday in 1968.

What sometimes gets overlooked in current discussions is that we neither commemorate Columbus’ birthday (as is the practice for many public figures) nor his death date (when Christian saints are usually memorialized), but rather the date of his arrival in the New World.

Columbus Day marks the first encounter that brought together the original and future Americans. A lot of suffering followed Columbus’ landing on San Salvador, and a lot of achievement, too. It was a momentous, world-changing occasion, such as has rarely happened in human history.

*****

WILLIAM J. CONNELL holds the La Motta Chair in Italian Studies at Seton Hall University. He is author and editor of several books, including the Routledge History of Italian Americans (2018).

No comments:

Post a Comment