The Pope's Monthly Intentions for 2024

November

For anyone who has lost a child

We pray that all parents who mourn the loss of a son or daughter find support in their community and receive peace and consolation from the Holy Spirit.

reflections, updates and homilies from Deacon Mike Talbot inspired by the following words from my ordination: Receive the Gospel of Christ whose herald you have become. Believe what you read, teach what you believe and practice what you teach...

For anyone who has lost a child

We pray that all parents who mourn the loss of a son or daughter find support in their community and receive peace and consolation from the Holy Spirit.

Other Titles: All Saints Day

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Share

Share Pin

Pin Email

Email

November 01, 2024 (Readings on USCCB website)

Solemnity of All Saints: Almighty ever-living God, by whose gift we venerate in one celebration the merits of all the Saints, bestow on us, we pray, through the prayers of so many intercessors, an abundance of the reconciliation with you for which we earnestly long. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, God, for ever and ever.

» Enjoy our Liturgical Seasons series of e-books!

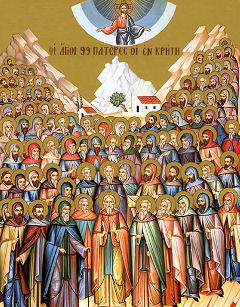

Today is the Solemnity of All Saints. The Church celebrates all the saints: canonized or beatified, and the multitude of those who are in heaven enjoying the beatific vision that are only known to God. During the early centuries the Saints venerated by the Church were all martyrs. Later the pope set November 1 as the day for commemorating all the Saints. We all have this "universal call to holiness." What must we to do in order to join the company of the saints in heaven? We "must follow in His footsteps and conform [our]selves to His image seeking the will of the Father in all things. [We] must devote [our]selves with all [our] being to the glory of God and the service of [our] neighbor. In this way, the holiness of the People of God will grow into an abundant harvest of good, as is admirably shown by the life of so many saints in Church history" (Lumen Gentium, 40).

"This perfect life with the Most Holy Trinity—this communion of life and love with the Trinity, with the Virgin Mary, the angels and all the blessed—is called "heaven." Heaven is the ultimate end and fulfillment of the deepest human longings, the state of supreme, definitive happiness" (CCC 1024).

Remember to pray for the Faithful Departed from November 1 to the 8th.

All Saints Day During the year the Church celebrates one by one the feasts of the saints. Today she joins them all in one festival. In addition to those whose names she knows, she recalls in a magnificent vision all the others "of all nations and tribes standing before the throne and in sight of the Lamb, clothed with white robes, and palms in their hands, proclaiming Him who redeemed them in His Blood."

During the year the Church celebrates one by one the feasts of the saints. Today she joins them all in one festival. In addition to those whose names she knows, she recalls in a magnificent vision all the others "of all nations and tribes standing before the throne and in sight of the Lamb, clothed with white robes, and palms in their hands, proclaiming Him who redeemed them in His Blood."

The feast of All Saints should inspire us with tremendous hope. Among the saints in heaven are some whom we have known. All lived on earth lives like our own. They were baptized, marked with the sign of faith, they were faithful to Christ's teaching and they have gone before us to the heavenly home whence they call on us to follow them. The Gospel of the Beatitudes, read today, while it shows their happiness, shows, too, the road that they followed; there is no other that will lead us whither they have gone.

According to various authors including Father Francis X. Weiser, SJ, the "Commemoration of All Saints" was first celebrated in the East. The feast is found in the West on different dates in the eighth century. The Roman Martyrology mentions that this date is a claim of fame for Gregory IV (827-844) and that he extended this observance to the whole of Christendom; it seems certain, however, that Gregory III (731-741) preceded him in this. At Rome, on the other hand, on May 13, there was the annual commemoration of the consecration of the basilica of St. Maria ad Martyres (or St. Mary and All Martyrs). This was the former Pantheon, the temple of Agrippa, dedicated to all the gods of paganism, to which Boniface IV had translated many relics from the catacombs. Gregory VII transferred the anniversary of this dedication to November 1.

Highlights and Things to Do:

Visiting a Church on November 2: A plenary indulgence, applicable only to the souls in purgatory, is granted to the faithful who, on All Souls' Day (or, according to the judgment of the ordinary, on the Sunday preceding or following it, or on the solemnity of All Saints), devoutly visit a church or an oratory and recite an Our Father and the Creed.

Praying for the Faithful Departed: A partial indulgence, applicable only to the souls in purgatory, is granted to the faithful who,

Indulgence Requirements:

|

|

|

|

|

![]()

By Kate Scanlon

OSV News

WASHINGTON (OSV News) — Catholic voters are among the key constituencies that candidates are seeking to win in 2024, as surveys and analysts indicate they are on track to be closely divided at the polls.

Catholic voters as a whole have varied in recent presidential elections about which party most of them choose to support. For example, data from the Pew Research Center found that most Catholic voters supported former President Donald Trump in 2016, but more Catholics voted for President Joe Biden in 2020.

Margaret Susan Thompson, an associate professor of history at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship & Public Affairs, who has studied the intersection of religion and politics in the U.S., told OSV News, “We know that Catholics are probably as divided as the rest of the electorate right now.”

“The election is extremely close by almost any standard and Catholics seem to be in many ways mirroring the American population in that regard,” she said.

Polls of the 2024 contest have shown conflicting data about Catholic voters, but also that similar trends are playing out in this constituency compared to the electorate as a whole.

A poll by the Pew Research Center in September found Trump leading Vice President Kamala Harris 52%-47% among Catholic voters. But Pew’s survey differed from an EWTN News/RealClear Opinion Research survey of Catholic U.S. voters conducted Aug. 28-30, which found 50% of Catholic voters said they plan to support Harris for president, while 43% said they planned to support Trump, with another 6% undecided.

Another poll of Catholic voters in seven battleground states — Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — by the National Catholic Reporter found these voters favored Trump over Harris 50 percent to 45 percent, with a margin of error of plus or minus 2.86 percent.

But most of those same polls also found partisan gaps widened when divided by demographics such as race and gender. While majorities of white Catholics favored Trump, majorities of Black and Hispanic Catholics said they would support Harris.

Thompson said that the Catholic vote in recent decades has grown less distinct from that of the general electorate, and “Catholics are very representative of the American population these days.”

“I think a lot of Catholics are going to vote for Harris, a lot of Catholics are going to vote for Trump,” she said. “And I don’t know how many of them are going to vote for Harris or Trump because they are Catholic.”

Catholic experts who have spoken with OSV News have alternately drawn points of agreement and tension between the platforms of Harris and Trump with respect to Catholic social teaching, on issues ranging from abortion and in vitro fertilization to immigration to climate and labor.

Pope Francis in September cast the upcoming U.S. election as a choice between the “lesser of two evils,” citing tension with the candidates’ platforms on immigration and abortion as “against life.”

But despite this tension, both campaigns have courted Catholic voters and launched Catholic coalitions. The Trump campaign has on social media made some cultural signals to Catholics, for instance, tweeting the St. Michael prayer. His running mate, Sen. JD Vance, R-Ohio, is also a convert to Catholicism. Trump and his surrogates have also labeled Harris as anti-Catholic, pointing to her work as a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee in 2018, when she scrutinized the nominations of some potential judges over whether their membership in the “all-male” Knights of Columbus, a Catholic charitable organization, could impact their ability to hear cases “fairly and impartially,” citing the organization’s opposition to abortion.

The Harris campaign, Thompson said, has been less overt in targeting specifically Catholic voters, but is trying “to retain the votes that President Biden received” in 2020. Biden, whom Harris serves under, is the country’s second Catholic president.

“I do think one area where the Catholic Church position may — and I really emphasize ‘may’ not ‘will’ — help the Democrats is on immigration,” she said, arguing that the U.S. bishops have long advocated for humane immigration policy and treatment of migrants, even those bishops who sometimes otherwise appear “generally pretty conservative.”

“And of course, so has the Holy Father,” she added, referring to Pope Francis.

Courting Catholic voters was also on display Oct. 17 at the annual Al Smith Memorial Foundation Dinner, a long-standing white-tie fundraiser benefiting Catholic charities. The dinner has a long tradition of welcoming both major party presidential candidates in election years, where the rivals typically exchange lighthearted jabs at one another. But this year, Harris declined to attend the event, sending a video message in which she praised “the tremendous charitable work of the Catholic Church.”

Thompson said that although Trump was in attendance at the event, his remarks included vulgarities and differed from the traditional format of light humor about the other candidate. For example, in 2008, then Sens. Barack Obama and John McCain teased one another but also offered remarks noting their respect for their rival, with Obama praising the “honor and distinction” of McCain’s military service, and McCain praising the historic nature of Obama’s candidacy and his “skill, energy and determination” to achieve it.

Harris instead spent that evening campaigning in Wisconsin, one of the three Rust Belt states along with Michigan and Pennsylvania that are seen as key battlegrounds in 2024.

Of those states, Pennsylvania, nicknamed the Keystone State, might live up to its nickname as the key contest in determining whether Trump or Harris secures the 270 Electoral College votes necessary to be elected president. A significant share of that state’s electorate is Catholic.

Micheal Allison, professor and chair of the Department of Political Science at the University of Scranton, said the area has a sizable Catholic population. It includes descendants of “particularly European Catholics who came over 100 years ago, 130 years ago,” and then those whose more recent relatives, or they themselves, immigrated to the area, he said, including “a lot from Latin America.”

Asked about how Biden carried both Catholic voters and Pennsylvania in 2020, Allison told OSV News that Biden was arguably “the right person at the right time,” someone who was seen as “a safe, moderate to conservative Democrat, up against someone who had overseen a pretty rough to worse time, particularly under COVID.”

Exit polling from 2020 found that 30 percent of Pennsylvania voters that year said they were Catholic. Allison said that shows “Catholic voters are going to show up.”

“I think they’re committed to voting,” he said. But he added that “the Catholic population is dwindling.”

“A lot of Catholics — people (who) are baptized and raised Catholic — don’t attend Mass,” he said. “There’s been some alienation from the Catholic Church. So, it’s not entirely always clear what people mean (in polling) when they say they’re Catholic, and they’re filling out exit polling, versus how regularly they attend church.”

Pennsylvania, he said, also has strong union ties, which can impact the voting habits of some who might otherwise be more socially conservative.

Thompson added that Catholics, like many voters, likely “have their positions pretty well solidified by now,” but pointed to controversial remarks at an Oct. 27 Trump rally at Madison Square Garden that generated headlines after a comedian who spoke there called Puerto Rico a “floating island of garbage,” among other controversial remarks about Latinos and other groups, as something that could affect how the remaining undecided Catholics ultimately vote.

Noting that “a sizable proportion of that population is Catholic,” Thompson said, “Is that going to persuade an undecided Catholic voter to say, ‘Well, having heard that, I’m definitely going to vote for the Republicans?’ Frankly, I don’t think so.”

Election Day is Nov. 5.

By Deborah Castellano Lubov

Pope Francis urged educators to push forward and never get discouraged, in the Vatican on Thursday, as he addressed participants in the 11th edition of Catholic Action's National Congress of the Movement for Educational Engagement (MIEAC).

"Without love, one cannot educate," the Pope stressed to those before him, imploring: "Always educate with love!"

The Pope thanked Italy's Catholic Action for building associations within the Church, and observed that the Movement's commitment to education today faces more challenges than ever before.

"To educate — as you well know and testify — means, above all, rediscovering and valuing the centrality of the person," he said, particularly "in a relational context where the dignity of human life finds fulfillment and proper space to grow."

Catholic Action's Education Project, he recalled, develops with an organic and systematic vision of the educational mission.

In this sense, he commended their dedicating themselves to this task with creativity, attention to the signs of the times, and allowing themselves to be enlightened by the Gospel, especially amid secularization which often threatens values and notions.

Looking ahead to the next Jubilee, the Pope gave them a task.

"Pay special attention to children, adolescents, and young people," he said, urging them to be looked at "with trust," "empathy," and "the gaze and heart of Jesus."

Since they are "the present and future of the world and the Church," the Holy Father said, "It is our task — a fully educational task — to accompany them, support them, encourage them, and, through our example, show them the right path that leads to being 'all brothers.'"

"Many urgent matters face us today, but one of the most pressing," he said, is to be "educators with a big heart," "for the good of the children, young people and adults" they attend to, amid all the "'labyrinths of complexity' that exist."

As the Pope called for collaborating among families, teachers, social leaders, sports coaches, catechists, priests, religious, public institutions, and young people themselves, he said, young people "must be involved," "active," and "never passive," in the educational process.

The Pope thanked the Movement for renewing their commitment to promoting education that truly places the person at its center, and never compromises their worth and dignity.

Pope Francis concluded by urging the delegation to go forward in its endeavours and entrusting them to the intercession of the Venerable Giuseppe Lazzati, "a credible teacher and witness" and a "model" for Christian educators.

By Joseph Tulloch

Communication, says Pope Francis, should aim “to build bridges where many build walls; to foster community where many deepen divisions; to engage with the tragedies of our time, where so many prefer indifference.”

The Pope made these remarks in a meeting with participants in the plenary assembly of the Vatican’s Dicastery for Communications, which brings together all the Holy See’s communications bodies, including Vatican News.

He added a request: Vatican communications should, “in a context of war, socio-economic inequality, consumerism, and dehumanising technology”, help individuals to “rediscover what is most important and essential: the heart.”

In their role as ambassadors of truth, justice, and peace, the Pope said, Church communicators should not forget their ecclesial identity: “If we think and act by political or business standards, we are not the Church. If we apply worldly criteria or reduce our structures to bureaucracy, we are not the Church."

“I dream”, the Pope said, “of a form of communication that can connect people and cultures. I dream of a form of communication capable of sharing stories and testimonies from every corner of the world."

“I dream of heart-to-heart communication, of being moved by what is human, by the tragedies so many of our brothers and sisters experience. I dream of a form of communication that teaches people to let go of a little bit of themselves to make space for others; a communication that is passionate, curious, and competent, that knows how to immerse itself in reality in order to tell it.”

Like Jesus, Catholic journalists should especially attend to the stories of the marginalized, the poor, migrants, and victims of war, telling these stories authentically and without “slogans.”

Their work, the Pope said, should promote inclusion, dialogue, and peace, including through reports on peace efforts worldwide: “How urgent it is to give space to peacemakers! Do not grow tired of telling their stories.”

The Pope encouraged the Dicastery to “venture out more, to dare more, to take more risks.”

This, he said, is not about promoting one’s own ideas but about “telling reality with honesty and passion.”

He encouraged his media professionals not to fear trying new things, exploring “new languages” and “new avenues” in digital spaces.

Implementing a synodal approach to communication is also essential, he added.

And all of this, the Pope emphasized, will need to happen without additional funding. “We must become a little more disciplined with money. You will need to find ways to save more and to look for other resources … I know this is difficult news, but it is also good news, because it inspires creativity.”

The Pope specifically praised the Dicastery’s efforts to expand the range of languages offered by Vatican News, which has recently expanded to offer content in Lingala, Mongolian, and Kannada.

And Pope Francis also expressed his thanks in advance for the immense energy that Vatican Media will put into covering the upcoming Jubilee year 2025. Thanks to the Vatican communications, he said, many who cannot travel to Rome physically will still be able to participate in the Holy Year.

Wolfgang (d. 994) + Bishop and reformer. Born in Swabia, Germany, he studied at Reichenau under the Benedictines and at Wurzburg before serving as a teacher in the cathedral school of Trier. He soon entered the Benedictines at Einsiedeln (964) and was appointed head of the monastery school, receiving ordination in 971. He then set out with a group of monks to preach among the Magyars of Hungary, but the following year (972) was named bishop of Regensburg by Emperor Otto II (r. 973-983). As bishop, he distinguished himself brilliantly for his reforming zeal and his skills as a statesman. He brought the clergy of the diocese into his reforms, restored monasteries, promoted education, preached enthusiastically, and was renowned for his charity and aid to the poor, receiving the title Eleemosynarius Major (Grand Almoner). He also served as tutor to Emperor Henry II (r. 1014-1024) while he was still king. Wolfgang died at Puppingen near Linz, Austria. He was canonized in 1052 by Pope St. Leo IX (r. 1049-1054). Feast day: October 31.