Pope Francis: 'Forgiveness is a human right'

By Salvatore Cernuzio

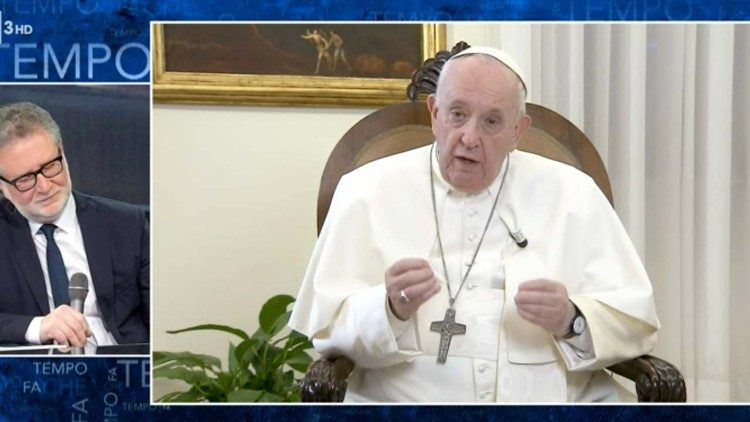

“War is a contradiction,” said Pope Francis during his conversation on Sunday night with Italian television presenter Fabio Fazio on the programme Che tempo che fa.

Speaking from his residence at the Casa Santa Marta, Pope Francis answered questions about a wide variety of issues: wars, migrants, safeguarding creation, the relationship between parents and children, evil and suffering, prayer, the future of the Church, and the need for friends. He also affirmed that forgiveness is “a human right,” adding, “the ability to be forgiven is a human right. We all have the right to be forgiven if we ask for forgiveness.”

Migration

The focus was primarily on migration, a theme dear to the Pope — a theme that, tragically, is still topical after the recent news of the twelve migrants found dead of frostbite on the border between Greece and Turkey. For the Pope, “this is a sign of the culture of indifference.” And it is also “a problem of categorisation”: wars, in first place; people, in second place.

Yemen is an example, he said: “How long has Yemen been suffering from war and how long have we been talking about the children of Yemen? A clear example, and there has been no solution to the problem for years. I don’t want to exaggerate, more than seven for sure, if not ten. There are categories that matter, and others are at the bottom: children, migrants, the poor, those who have no food. These don’t count, at least they don’t count in the first place, because there are people who love these people, who try to help them, but in the universal imagination what counts is war, the sale of weapons. Just think that with a year without making weapons, you could give food and education to the whole world, free of charge. But this is in the background,” said Pope Francis.

He then turned his thoughts to Alan Kurdi, the little Syrian boy found dead on a beach, and to the many other children like him “whom we do not know” and who “die of cold” every day. War remains, however, the primary category: “We see how economies are mobilised and what is most important today, war: ideological war, war of powers, commercial war and so many arms factories,” the Pope said.

War

And speaking of war, the Pope — when asked about the ongoing tensions between Ukraine and Russia — recalls the roots of this horrible reality, which he called “a contradiction of creation”, which go back to Genesis, with the ‘war’ between Cain and Abel, and that of the Tower of Babel.

“Wars between brothers” appeared shortly after God’s creation of man and woman, he said.

Criminal treatment of migrants

Pope Francis places the “criminal” treatment reserved for thousands of migrants within the same dynamic. In order to reach the sea “they suffer so much,” said the Pope. Once again, he denounced the “concentration camps” in Libya, lamenting “how much those who wish to flee suffer in the hands of traffickers.” There are films that show this, he said, including many that can be found in the Migrants and Refugees Section of the Dicastery for Human Development.

“They suffer and then they risk crossing the Mediterranean. Then, sometimes, they are rejected by someone who, out of a sense of local responsibility says ‘No, they can’t come here'; there are these ships that go around looking for a port, that have to return [to where they came from] or they die at sea. This is happening today,” the Pope reiterated.

As he has done on other occasions, he repeated the principle that “each country must determine how many migrants it can accept.” This, the Pope said, “is a problem of internal politics that must be considered thoroughly,” with the different countries coming up with different numbers. “And the others?” he asked? “There is the European Union, we have to agree, so we can achieve a balance, in communion.” Instead, only “injustice” seems to emerge: “They come to Spain and Italy, the two closest countries, and they are not received elsewhere,” he said.

Pope Francis repeated four key words that he has consistently emphasized: “The migrant must always be welcomed, accompanied, promoted and integrated. Welcomed because there are difficulties, then [there is a need of] accompanying, promoting, and integrating them into society.” Above all, he insisted, it is necessary to integrate them into the receiving countries to avoid ghettoization and extremism born of ideologies.

Divisions in the world

Asked about this point by the presenter, Pope Francis urged his listeners to reflect on what seems to be a tremendous division in the world – a division that sees one part of the world developed, where people have “the possibility of school, university, work”; and another part where “children dying, migrants drowning, injustices that we see also in our own countries.” There is a very “ugly” temptation, to look the other way, to avoid looking at the needs of others.

The Pope acknowledged that media outlets show what is happening in the world – but complained that “we take distance,” we draw back from the realities that we see.

“We complain a little, [saying] ‘It’s a tragedy!’ but then it’s as if nothing had happened,” he said. “It is not enough to see, it is necessary to feel, it is necessary to touch,” Pope Francis insisted. “We miss ‘touching’ the miseries; touching leads us to heroism. I think of the doctors and nurses who gave their lives in this pandemic: they touched the evil and chose to remain with the sick.”

Care for creation

The same principle applies to the Earth, he said. Once again, Pope Francis reiterated his call to care for creation, saying, “It’s a lesson we have to learn.” The Pope pointed to the Amazon and the problems of deforestation, lack of oxygen, climate change, noting there is a risk of “the death of biodiversity,” a risk of “killing Mother Earth.”

Turning his gaze closer to Italy, he pointed to the example of the fishermen of San Benedetto del Tronto, who discovered some three million tonnes of plastic in one year and took action to remove all waste from the sea. “We have to get it into our heads: we must take care of Mother Earth,” the Pope said.

An attitude of care

Pope Francis called for an attitude of “care,” which, he said, also seems to be lacking from a social point of view. What we are experiencing today is in fact a problem of “social aggression,” as seen with the phenomenon of bullying.

With the focus still on young people — who, despite being hyper-connected, sometimes suffer “an incredible sense of loneliness” — Pope Francis spoke directly to parents of teenagers, who sometimes struggle to understand “the suffering of others.”

For the Bishop of Rome, the relationship between parents and children can be summed up in one word: “closeness.”

He insisted on the importance of “generosity with one’s children: playing with the children and not being frightened of the children, of the things they say, of their speculations; or even staying close to an older child, an adolescent when they slip up, speaking to them as a father, as a mother.”

Closeness

On the subject of ‘closeness,’ Mr Fazio, the interviewer, brought up a well-known saying of Pope Francis: “The only reason a person should look down on another person is to help him up.”

“It’s true,” the Pope said. “In society, we see how often people look down on others to dominate them, to subdue them, instead of helping them get up.” He continued, “Just think — it’s a sad tale, but an everyday story — of those employees who have to pay the price of job stability in their own bodies, because their bosses look down on them, domineering.” But on the other hand, the act of looking at another from above is only permissible in order to do a “noble” act, namely to hold out one’s hand and say, “Stand up brother, stand up sister.”

Freedom

The conversation expanded to touch on larger topics, including the concept of freedom, which, the Pope said, is a gift from God, but which “is also capable of doing much evil.” He said, “Since God made us free, we are masters of our decisions, and are also [capable] of making wrong decisions.”

The Pope also dwelt on the concept of evil. “Is there anyone who does not deserve God’s forgiveness and mercy or the forgiveness of men?” the presenter asked.

Pope Francis warned that his answer might “shock some people”. “The ability to be forgiven is a human right.”

Evil

But there is another kind of evil, he said, the evil that sometimes strikes the innocent, and that seems inexplicable, causing people to wonder why God does not intervene.

“So many evils,” explained the Bishop of Rome, “come about precisely because man has lost the ability to follow the rules, has changed nature, has changed so many things, but also because of his own human frailties. And God allows this to go on,” he said. But some questions remain unanswered: “Why do children suffer?”

Pope Francis admitted, “I can find no explanation for this. I have faith, I try to love God who is my Father, but I ask myself, ‘But why do children suffer?’ And there is no answer. He is powerful, yes, omnipotent in love. On the contrary, hatred and destruction are in the hands of another who through envy has sown evil in the world.”

Future of the Church

The future, of the world and of the Church, took up a good part of the interview. The future of the world, as foreshadowed in Fratelli tutti, with humanity at the centre of economies and choices. This is a priority that the Pope says he shares with many heads of state who have good ideals. These, however, clash with “political and social conditioning, even in world politics, which put an end to good intentions”. These are “shadows” that put pressure on society, on the people, on those who have roles of responsibility. “And then,” the Pope said, “you have a lot of negotiating to do.”

On the future of the Church, Pope Francis recalled the image of the Church outlined by St Paul VI in the apostolic exhortation Evangelii nuntiandi, the inspiration for his own Evangelii gaudium: “A Church on pilgrimage.”

Today “the greatest evil facing the Church, the greatest,” Pope Francis said emphatically, “is spiritual worldliness” which, in turn, “gives rise to a bad thing: clericalism, which is a perversion of the Church.” He pointed specifically to the clericalism found in “rigidity,” insisting that “underneath every kind of rigidity there is rottenness, always.” Among the “ugly things” in the Church today, the Pope noted “rigid, ideologically rigid positions” that take the place of the Gospel.

“Concerning pastoral attitudes,” he said, “I will mention only two, which are old: Pelagianism and Gnosticism.” Pelagianism, he explained, “is believing that I can go forward through my own power.” On the contrary, he said, “the Church goes forward with the strength of God, the mercy of God, and the power of the Holy Spirit.” He described Gnosticism, as a kind of mysticism, “without God,” an “empty spirituality.”

Instead, he asserted, “without the flesh of Christ there is no possible understanding; without the flesh of Christ there is no possible redemption.” Pope Francis said, “We must once again return to the centre ‘The Word was made flesh.’” The future of the Church, he said, lies “in this scandal of the Cross, of the Word made flesh.”

Prayer

Pope Francis went on to explain the importance of prayer. “Praying is what a child does when he feels limited, powerless,” he said, like a child calling out “daddy, mommy.” Praying, the Pope said, means recognizing “our limits, our needs, our sins.... To pray is to enter with strength, beyond the limits, beyond the horizon, and for us Christians to pray is to encounter ‘papa’.”

“The child,” insisted the Pope, “does not wait for daddy’s answer; when the dad begins to answer, he goes on to another question. What the child wants is for his father’s gaze to be on him. It doesn’t matter what the explanation is, it only matters that papa is looking at him, and that gives him security. Praying is a bit of all this.”

Friends

The questions for the Pope also touched on more personal matters: “Do you ever feel lonely?” Mr Fazio asked. “Do you have real friends?”

Pope Francis answered affirmatively: “Yes, I have friends who help me; they know my life like a normal guy — not that I am normal, no. I have my own abnormalities and they know me well. I have my own abnormalities, eh, but like an ordinary man who has friends; and I like to be with my friends, sometimes to tell them my concerns, [sometimes] to listen to theirs, but really, I need friends. That’s one of the reasons why I didn’t go to live in the papal apartments, because the popes who were there before were saints, but me not so much, I’m not that much of a saint. I need human relationships, that’s why I live in this residence of Santa Marta where you find people who talk with everyone, you find friends. It’s an easier life for me; I don’t feel up to the other one; I don’t have the strength and friendships give me strength. I actually need friends, they aren’t many, but they’re true friends.”

There was no lack of references to the past in the conversation, to his childhood in Buenos Aires, his support for the San Lorenzo football team, his ‘vocation’ as a butcher, his roots in the Italian region of Piedmont, and his experience in the chemistry laboratory — a study, he said, that “seduced” him greatly, but over which the call of God prevailed.

Pope Francis also recalled the vow he made to Our Lady of Carmel, on 16 July 1990, not to watch TV. “I don’t watch television,” he said, “but not because I condemn it.” He spoke, too, about his love of music, especially classical music; and reflected on his sense of humour, which he said, “is a medicine” that “does so much good.”

No comments:

Post a Comment