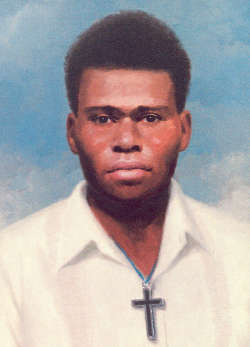

Bl. Peter To Rot

Facts

Peter To Rot was born in 1912 in Rakunai, a village near Rabaul, the capital of New Britain. To Rot's father was Angelo To Puia, a respected chief and local leader, and his mother was Maria Ja Tumul. Peter was the third of six children. There was an older brother and sister, Joseph and Therese, a younger brother, Gabriel, and the two youngest, a boy and a girl, who died in childhood.

Peter was his father's favorite, probably because they had similar personalities and characteristics. But To Puia did not spoil his son and required as much of him as of the others. When Peter was seven, his father sent him to the village school, even though school was not mandatory. He knew the value of education if Peter was to become a leader. At school, Peter showed himself a quick and able student. His teachers noted that his journal of activities of the previous day always included morning and evening prayer.

When Peter was 18, the parish priest, Fr. Laufer, MSC, spoke to his father about the possibility of To Rot becoming a priest. Angelo To Puia responded that he thought it was not yet time for one of their generation to become a priest. Perhaps one of his grandchildren would be that lucky. However he agreed that Peter could become a catechist. And so in the fall of 1930, Peter went to study at the Catechist School in Taliligap, staffed by the MSC.

Peter applied himself fully to the studies. His prayer life grew with daily participation in Mass and Communion, regular stops at church to pray during the day, and increased devotion to the Blessed Sacrament. At Taliligap his leadership abilities flowered in work, sports, recreation and prayer.

Before the end of his third year at school, Fr. Laufer sent word that he was urgently needed at the parish. To Rot returned to Rakunai and, at 21 years of age, became the youngest catechist. His main work was teaching in the parish school; but he also visited and prayed with the sick. People liked him because he was even-tempered, never moody, calm and kind. He defended the church and its teachings, engaging anyone is conversation about religion. People soon learned that he practiced what he preached.

On November 11, 1936, Peter married Paula Ja Varpit at the Rakunai church. Paula had been a student in Peter's classes and their two families arranged the wedding. Their marriage was a happy one. To Rot was an exemplary husband and they prayed together every morning and evening. He would often confide in Paula, especially as his concerns increased during the Japanese occupation.

Their first child was born on December 5, 1939. They named him To Puia, in honor of To Rot's father who had died in 1937 and gave him the Christian name of Andreas. Peter was a very proud father and often carried the child around with him, holding him and playing with him. Andreas spent more time with his father than his mother, an unusual fact in the culture. In 1942 a girl, Rufina, was born.

To Rot willingly took on this work, even though he was afraid. He knew that God would be with him. He visited the sick, prayed with those who were dying, and prepared them to meet Jesus. He held classes for both children and adults. He helped them all to remain loyal to the teachings of Jesus. To those who were frightened by the events of the war, To Rot would encourage them saying, "This is a very bad time for us, and we are all afraid. But God our Father is with us and looking after us. We must pray and ask him to stay with us always."

Peter was also in the habit of gathering the villagers together every day for prayer. But when the bombings increased, they decided that it was unwise for them all to meet in one place. To Rot divided the people into small groups and had them meet in the caves that had been made for hiding from the bombs. The people continued their daily prayers in these caves and were filled with strength and peace, despite the dangers all around them.

Early on, the Japanese paid no attention to the people's prayer and Sunday worship. But when they started losing the war, they feared that the people's God was against them. They called in the village leaders and commanded them, "You people must not pray to your God. You cannot meet on Sundays for service, and you must not pray in the villages either. Anyone who disobeys this law will go to jail."

When the leaders brought the message from the Japanese back to their villages, it was Peter To Rot who spoke up, "The Japanese cannot stop us loving God and obeying his laws! We must be strong and we must refuse to give in to them." And so he continued to teach the people and gather them for prayer.

Another of the Japanese laws was that men could take a second wife. They wanted to gain favor with the locals and control them more easily. Again Peter To Rot objected and reprimanded anyone found with a second wife. He insisted that the villagers follow the Church's teaching about marriage and that they come to him, their catechist, to witness the marriages. Anything else was a sin before God. On several occasions he made provisions for the care of women who were being abducted to become second wives.

The Japanese police chief first interrogated the older brother, Tatamai, about church services. When Tatamai answered that he had indeed attended church services, the police chief struck him on the head with a wooden cane and sentenced him to one month in prison.

Then To Rot was interrogated about celebrating church services, his attitude concerning marriage, and his defiance of the Japanese law allowing more than one wife. To Rot was also struck on the head and repeatedly poked with the cane in his upper chest, around the heart. He was sentenced to two months in prison.

Telo, the youngest, was accused of being an Australian spy because of the bank book. He was hung on a papaya tree and beaten till he lost consciousness. In the days following, Tatamai and To Rot were sent into forced labor; Telo had been too severely beaten to work.

Telo was released after two weeks because of his health after the beating; Tatamai was released after a month; but To Rot was kept at the prison. When To Rot's village chief asked the police why he was not released, he was told that To Rot was a bad type who prevented men from having two wives and who called people to prayer.

To Rot had many visits from relatives and friends, especially his mother and his wife. They came every day and brought him food. He would encourage them and assure them that he was not afraid because he was in prison for God. To the village chief who came to see him, Peter said, "I am in prison because of the adulterers and because of the church services. Well, I am ready to die. But you must take care of the people." To another friend, Peter added, "If it is God's will, I'll be murdered for the faith. I am a child of the church and therefore for the church I will die."

Later in the day when his mother came to visit, To Rot told her that the police were having a Japanese doctor come to give him some medicine (he had developed a slight cold). But he added, "I don't know what that means. Perhaps it is a lie. After all, I am not ill." Late in the afternoon, To Rot bathed, shaved and put on his new laplap. He stood at the door of the prison hut and prayed.

Around 7 in the evening, all the prisoners--except To Rot--were taken to a nearby farm for a party. They were surprised since this had never happened before. At about 10 o'clock, the Japanese guard told them to go to sleep. Not returning to the prison for the night was also very unusual. Because security was very light, three prisoners crept back to the prison in the darkness. There they found Peter To Rot dead on the porch of the prison house.

To Rot was on his back, one arm bent under his head, and one leg twisted at an angle under the other. His body was still warm. They noticed cotton wads in his nostrils and ears, a red welt on his neck, a strip of cloth around his head, and a small puncture hole from a syringe on his upper left arm. They knew he had been murdered, but fearing for their own lives, hid and said nothing.

In the morning at roll call, To Rot was missing and the Japanese chief sent someone to check on him. The police chief feigned surprise at To Rot's death and said that he had been very ill and must have died. Then he sent for the village chief and To Rot's relatives to come and take away the body.

Peter To Rot was given a chief's burial at the new cemetery next to the church where he had ministered. Even though many people came, the funeral was held in silence, fearing what the Japanese might do if the people prayed aloud and in public. From that day on he was revered as a martyr for his faith.

No comments:

Post a Comment