Spy Wednesday conversion to Holy Wednesday

One of the Twelve, who was called Judas Iscariot,

went to the chief priests and said,

"What are you willing to give me

if I hand him over to you?"

They paid him thirty pieces of silver,

and from that time on he looked for an opportunity to hand him over.

On the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread,

the disciples approached Jesus and said,

"Where do you want us to prepare

for you to eat the Passover?"

He said,

"Go into the city to a certain man and tell him,

'The teacher says, "My appointed time draws near;

in your house I shall celebrate the Passover with my disciples."'"

The disciples then did as Jesus had ordered,

and prepared the Passover.

When it was evening,

he reclined at table with the Twelve.

And while they were eating, he said,

"Amen, I say to you, one of you will betray me."

Deeply distressed at this,

they began to say to him one after another,

"Surely it is not I, Lord?"

He said in reply,

"He who has dipped his hand into the dish with me

is the one who will betray me.

The Son of Man indeed goes, as it is written of him,

but woe to that man by whom the Son of Man is betrayed.

It would be better for that man if he had never been born."

Then Judas, his betrayer, said in reply,

"Surely it is not I, Rabbi?"

He answered, "You have said so."

Wednesday's Gospel reading preludes the betrayal of Judas. How appropriate then is the sometimes used phrase of, "Spy Wednesday," for this period before our celebration of the Sacred Triduum. The events that lead Jesus to the cross are filled with intrigue, suspense and an impending sense of disaster.

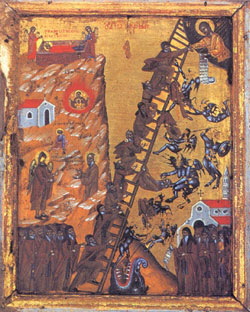

Clearly, the powers of good and evil, light and darkness, sin and salvation are poised to exhibit themselves at the place we call Golgotha. The Joannine account of Jesus betrayal seems to show Jesus' deep understanding of His role as the Messianic fulfillment. Judas in his interrogatory and somewhat cynical half statement of,"Surely it is not I, Rabbi?" provides the catalyst for the process of darkness to unravel. What is so significant about this ,"Spy Wednesday" is that it theologically reflects the daily struggles we all endure in order to accept a relationship with the Lord.

To live the life that Jesus intended for us is a perpetual struggle on a daily basis with good and evil. Sometimes when we are questioned about our transgressions, we, sometimes answer back. "It's not me Lord." But the tranquility of Jesus' realization of His mission provides us with hope in the days to come. Rather than provide a discourse to the Twelve, Jesus calmly recalls the Old Testament references to Him and even shares a piece of food with Judas, simultaneously dipping a morsel into the bowl. We should remember that the act of sharing a meal with others is a deeply rooted Semite notion of intimacy and close relationship. Jesus is sharing the meal, not with strangers, but with intimate friends.

Often, we dip morsels and share food with those we love; we feign intimacy and even deceive one another. Jesus is not blind to the events that are revealing themselves as a result of Judas' clandestine negotiations. Judas has turned on Jesus' friendship and love. We too in our lives are sometimes turned against Jesus' love through sinful and unloving activities. There is a real message here in Jesus' tranquil resignation to the events that are coming. Faith in the love and power of the Father.

As believers in the power of God's love and goodness, Spy Wednesday, should provide a period for reflection and introspective prayer. We need to examine our lives and look for the moments that we have falsely shared intimacy with our brothers and sisters in faith. More precisely, contemplate of lack of true, "communio" in our lives. With Judas' false interrogatory response to Jesus, he reveals his true self. Betrayer. Jesus sees right through Judas' false piety and friendship. Jesus sees right through our own appearances when we falsely present ourselves as holy and faithful followers. Our frail human spirit reflects in our sinful acts and lack of faith.

Jesus recognizes this and offers new hope to Judas and us. The "morsel" which Jesus offers to Judas is an offering of friendship and love. Some biblical scholars have even indicated that the "morsel" is symbolic of Jesus' Eucharistic manifestation. Judas does not partake of the meal with Jesus, but he was invited just the same. There is a sense that Jesus recognizes Judas' confrontation with the powers of evil. Jesus does not admonish him or chastise him, but permits Judas to engage in this struggle and reveal the implications of his actions and unfaithfulness. There is hope for conversion. There is hope for grace. There is hope in Jesus' acceptance of the Father's plan. There is hope for Easter glory.

As preparations begin for the Church's celebration of our New Passover ,this Wednesday before the Triduum invites all of us to share in, "Holy Wednesday", not to pursue darkness and evil, but progress on the path of light and life. The Church in its wisdom sees this period of "Holy Wednesday" as a time for personal preparation. Unlike Judas, our preparations should be motivated by the promise of new life in the Paschal Mystery and not a rejection of the "morsel" which Jesus offers to us in friendship and love.

One of the Twelve, who was called Judas Iscariot,

went to the chief priests and said,

"What are you willing to give me

if I hand him over to you?"

They paid him thirty pieces of silver,

and from that time on he looked for an opportunity to hand him over.

On the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread,

the disciples approached Jesus and said,

"Where do you want us to prepare

for you to eat the Passover?"

He said,

"Go into the city to a certain man and tell him,

'The teacher says, "My appointed time draws near;

in your house I shall celebrate the Passover with my disciples."'"

The disciples then did as Jesus had ordered,

and prepared the Passover.

When it was evening,

he reclined at table with the Twelve.

And while they were eating, he said,

"Amen, I say to you, one of you will betray me."

Deeply distressed at this,

they began to say to him one after another,

"Surely it is not I, Lord?"

He said in reply,

"He who has dipped his hand into the dish with me

is the one who will betray me.

The Son of Man indeed goes, as it is written of him,

but woe to that man by whom the Son of Man is betrayed.

It would be better for that man if he had never been born."

Then Judas, his betrayer, said in reply,

"Surely it is not I, Rabbi?"

He answered, "You have said so."

Wednesday's Gospel reading preludes the betrayal of Judas. How appropriate then is the sometimes used phrase of, "Spy Wednesday," for this period before our celebration of the Sacred Triduum. The events that lead Jesus to the cross are filled with intrigue, suspense and an impending sense of disaster.

Clearly, the powers of good and evil, light and darkness, sin and salvation are poised to exhibit themselves at the place we call Golgotha. The Joannine account of Jesus betrayal seems to show Jesus' deep understanding of His role as the Messianic fulfillment. Judas in his interrogatory and somewhat cynical half statement of,"Surely it is not I, Rabbi?" provides the catalyst for the process of darkness to unravel. What is so significant about this ,"Spy Wednesday" is that it theologically reflects the daily struggles we all endure in order to accept a relationship with the Lord.

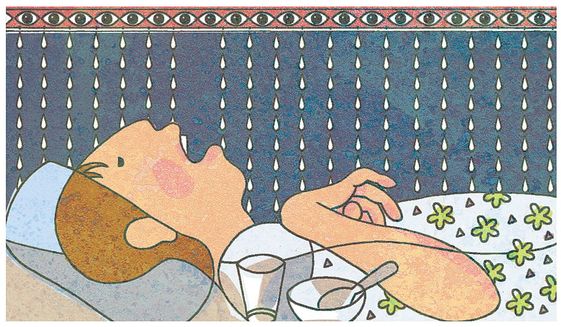

To live the life that Jesus intended for us is a perpetual struggle on a daily basis with good and evil. Sometimes when we are questioned about our transgressions, we, sometimes answer back. "It's not me Lord." But the tranquility of Jesus' realization of His mission provides us with hope in the days to come. Rather than provide a discourse to the Twelve, Jesus calmly recalls the Old Testament references to Him and even shares a piece of food with Judas, simultaneously dipping a morsel into the bowl. We should remember that the act of sharing a meal with others is a deeply rooted Semite notion of intimacy and close relationship. Jesus is sharing the meal, not with strangers, but with intimate friends.

Often, we dip morsels and share food with those we love; we feign intimacy and even deceive one another. Jesus is not blind to the events that are revealing themselves as a result of Judas' clandestine negotiations. Judas has turned on Jesus' friendship and love. We too in our lives are sometimes turned against Jesus' love through sinful and unloving activities. There is a real message here in Jesus' tranquil resignation to the events that are coming. Faith in the love and power of the Father.

As believers in the power of God's love and goodness, Spy Wednesday, should provide a period for reflection and introspective prayer. We need to examine our lives and look for the moments that we have falsely shared intimacy with our brothers and sisters in faith. More precisely, contemplate of lack of true, "communio" in our lives. With Judas' false interrogatory response to Jesus, he reveals his true self. Betrayer. Jesus sees right through Judas' false piety and friendship. Jesus sees right through our own appearances when we falsely present ourselves as holy and faithful followers. Our frail human spirit reflects in our sinful acts and lack of faith.

Jesus recognizes this and offers new hope to Judas and us. The "morsel" which Jesus offers to Judas is an offering of friendship and love. Some biblical scholars have even indicated that the "morsel" is symbolic of Jesus' Eucharistic manifestation. Judas does not partake of the meal with Jesus, but he was invited just the same. There is a sense that Jesus recognizes Judas' confrontation with the powers of evil. Jesus does not admonish him or chastise him, but permits Judas to engage in this struggle and reveal the implications of his actions and unfaithfulness. There is hope for conversion. There is hope for grace. There is hope in Jesus' acceptance of the Father's plan. There is hope for Easter glory.

As preparations begin for the Church's celebration of our New Passover ,this Wednesday before the Triduum invites all of us to share in, "Holy Wednesday", not to pursue darkness and evil, but progress on the path of light and life. The Church in its wisdom sees this period of "Holy Wednesday" as a time for personal preparation. Unlike Judas, our preparations should be motivated by the promise of new life in the Paschal Mystery and not a rejection of the "morsel" which Jesus offers to us in friendship and love.

AFP/ Pool

AFP/ Pool