The Catholic Church in Colonial America

Marian T. Horvat, Ph.D.

| Relatively little attention has been paid to the relentless hostility toward the Catholics of our 13 English colonies in the period that preceded the American Revolution. Instead, historians have tended to concentrate only on the story of the expansion of the tiny Catholic community of 1785, which possessed no Bishop and hardly 25 priests, into the mighty organization we see today that spreads its branches from the Atlantic to the Pacific. To show this progress of Catholicism is good and legitimate. But to avoid presenting the persecution the Church suffered in the pre-Revolution colonial period is to offer an incomplete or partial history. It ignores the early story of our Catholic ancestors. It would be like describing the History of the Church only after the Edict of Milan, when the Church emerged from the Catacombs, pretending there had never been a glorious but terrible period of martyrdom. An optimistic view that conflicts with reality It should not be surprising that this cloud of general omission concerning Catholicism in the colonial period (1600-1775) should have settled over the Catholic milieu given the optimistic accounts written by such notable Catholic historians as John Gilmary Shea, Thomas Maynard, Theodore Roemer, and Thomas McAvoy. (1) These historians, whose works provided the foundation for Catholic school history books up until recently (when a different kind of revisionist history is replacing them), only briefly acknowledge and downplay a period of repression and persecution of Catholics. What they have stressed is what might be called the "positive" stage of Catholic colonial history that begins in the period of the American Revolution. This period has been glossed with an unrealistic interpretation that freedom of religion was unequivocally established and the bitter, deeply-entrenched anti-Catholicism miraculously dissolved in the new atmosphere of tolerance and liberty for all. This in fact did not happen. Roots of a bad Ecumenism Here I propose to dispel this myth that America was from its very beginning a country that championed freedom of religion. In fact, in the colonial period, a virulent anti-Catholicism reigned and the general hounding and harrying of Catholics was supported by legislation limiting their rights and freedom.

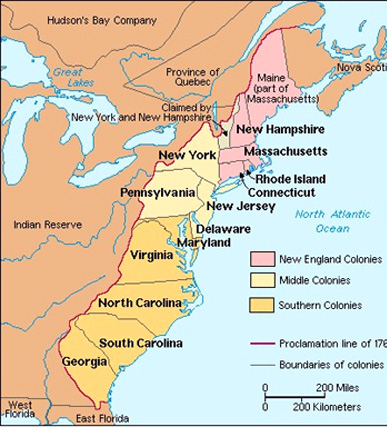

First, both before and especially after the American Revolution, a general spirit of tolerance to a Protestant culture and way of life was made by some Catholics in order to be accepted in society. Such accommodation, I would contend, has continued into our days. Second, to enter the realm of politics and avoid suspicions of being monarchists or “papists,” colonial American Catholics were prepared to accept the revolutionary idea of the separation of Church and State as a great good not only for this country, but for Catholic Europe as well. Both civil and religious authorities in America openly proclaimed the need to abandon supposedly archaic and “medieval positions” in face of new conditions and democratic politics. For these reasons, some hundred years after the American Revolution, Pope Leo XIII addressed his famous letter Testem benevolentiae (January 22, 1889) to Cardinal Gibbons, accusing and condemning the general complacence with Protestantism and the adoption of naturalist premises by Catholics in the United States. He titled this censurable attitude Americanism. Americanism, therefore, is essentially a precursory religious experience of bad Ecumenism made in our country, while at the same time Modernism was growing in Europe with analogous tendencies and ideas. The partial presentation of colonial American history by so many authors helps to sustain that erroneous ecumenical spirit. I hope that showing the historic hatred that Protestantism had for Catholicism can serve to help snuff out this Americanist – that is, liberal or modernist – behavior among Catholics of our country. A long history of anti-Catholicism Although Catholicism was an influential factor in the French settlements of the Ohio and Mississippi valleys and later in the Spanish regions of Florida, the Southwest and California, Catholics were a decided minority in the original 13 English colonies. As we see in the first general report on the state of Catholicism by John Carroll in 1785, Catholics were a mere handful. He conservatively estimated the Catholic population in those colonies to be 25,000. Of this figure, 15,800 resided in Maryland, about 7,000 in Pennsylvania, and another 1,500 in New York. Considering that the population in the first federal census of 1790 totaled 3,939,000, the Catholic presence was less than one percent, certainly not a significant force in the original 13 British colonies. (2)

The history of the Catholic Church in America, however, has much deeper and less triumphant roots. Most American Catholics are aware that the spirit of New England's North American settlements was hostile to Catholicism. But few are aware of the vigor and persistence with which that spirit was cultivated throughout the entire colonial period. Few Catholics realize that in all but three of the 13 original colonies, Catholics were the subject of penal measures of one kind or another during the colonial period. In most cases, the Catholic Church had been proscribed at an early date, as in Virginia where the act of 1642 proscribing Catholics and their priests set the tone for the remainder of the colonial period. Even in the supposedly tolerant Maryland, the tables had turned against Catholics by the 1700s. By this time the penal code against Catholics included test oaths administered to keep Catholics out of office, legislation that barred Catholics from entering certain professions (such as Law), and measures had been enacted to make them incapable of inheriting or purchasing land. By 1718 the ballot had been denied to Catholics in Maryland, following the example of the other colonies, and parents could even be fined for sending children abroad to be educated as Catholics. In the decade before the American Revolution, most inhabitants of the English colonies would have agreed with Samuel Adams when he said (in 1768): "I did verily believe, as I do still, that much more is to be dreaded from the growth of popery in America, than from the Stamp Act, or any other acts destructive of civil rights." (3) English hatred for the Roman Church The civilization and culture which laid the foundations of the American colonies was English and Protestant. England's continuing 16th and 17th-century religious revolution is therefore central to an understanding of religious aspects of American colonization. Early explorers were sent out toward the end of the 15th century by a Catholic king, Henry VII, but actual settlement was delayed, and only in 1607, under James I, were permanent roots put down at Jamestown, Virginia. By then, the separation of the so-called Anglican church from Rome was an accomplished fact.

International politics were involved too. France and Spain were England's enemies, and they were Catholic. In 1570 Pope St. Pius V excommunicated Elizabeth I and declared her subjects released from their allegiance, which fanned English propaganda that Catholic subjects harbored sentiments of treason. (4) In the 16th century, the English began their long, violent and cruel attempt to subdue the Catholics of Ireland. (5) The English were able “to resolve” any problem of conscience by convincing themselves that the Gaelic Irish Catholic Papists were an unreasonable and boorish people. Maintaining their false belief they were dealing with a culturally inferior people, the English Protestants imagined themselves absolved from all normal ethical restraints. This attitude persisted with their settlers in the American colonies. (6) To these factors should be added the role of the Puritan sect. Its relationship with Catholics in colonial America represented the apotheosis of Protestant prejudice against Catholicism. Even though the so-called Anglican church had replaced the Church of Rome, for many Puritans that Elizabethan church still remained too tainted with Romish practices and beliefs. For various reasons, those Puritans left their homeland to found new colonies in North America. A major Puritan exodus to New England began in 1630, and within a decade close to 20,000 men and women had migrated to settlements in Massachusetts and Connecticut. (7) They were principal contributors to a virulent hatred of Catholicism in the American colonies. The penal age: 1645-1763 Evidence of this anti-Catholic attitude can be found in laws passed by colonial legislatures, sermons preached by colonial ministers, and various books and pamphlets published in the colonies or imported from England. (8) When Georgia, the thirteenth colony, was brought into being in 1732 by a charter granted by King George II, its guarantee of religious freedom followed the fixed pattern: full religious freedom was promised to all future settlers of the colony “except papists,” that is Catholics. (10) Even Rhode Island, famous for its supposed policy of religious toleration, inserted an anti-Catholic statute imposing civil restrictions on Catholics in the colony's first published code of laws in 1719. Not until 1783 was the act revoked. (11) To have an idea of how this prejudice against Roman Catholics was impressed even among the young, consider these “John Rogers Verses” from the New England Primer: “Abhor that arrant whore of Rome and all her blasphemies; Drink not of her cursed cup; Obey not her decrees." This age of penal restriction against Catholics in the colonies lasted until after the American Revolution. Someone recalling a lesson from his Catholic history classes might pose the objection: But what about the exceptions to this rule, that is, the three colonial states of Maryland, New York, and Pennsylvania, where tolerance for Catholics existed in the colonial period? Once again, this impression comes from a very optimistic and liberal writing of History rather than the concrete reality. Catholicism in Maryland The "Maryland Experiment" began when Charles I issued a generous charter to a prominent Catholic convert from Anglicanism, Lord Cecil Calvert, for the American colony of Maryland. In the new colony, religious tolerance for all so-called Christians was preserved by Calvert until 1654. In that year, Puritans from Virginia succeeded in overthrowing Calvert's rule, although Calvert regained control four years later. The last major political uprising took place in 1689, when the ‘Glorious Revolution” of William and Mary ignited a new anti-Catholic revolt in Maryland, and the rule of the next Lord Baltimore, Charles Calvert, was overthrown.

The Religious Toleration Law of 1649 establishing toleration for all religions in early Maryland has generally been interpreted as resulting from the fact that Cecil Calvert was a Roman Catholic. Catholic American histories commonly presented the foundation of Maryland as motivated by Calvert's burning desire to establish a haven for persecuted English Catholics. On the other side are Protestant interpretations that present Calvert as a bold opportunist driven by the basest pecuniary motives. (13) More recent works have provided a much more coherent analysis of the psychology behind the religious toleration that Calvert granted. That is, Calvert was only following a long-standing trend of English Catholics, who tended to ask only for freedom to worship privately as they pleased and to be as inoffensive to Protestants as possible. A directive of the first Lord Proprietor in 1633 stipulated, for example, that Catholics should “suffer no scandal nor offence” to be given any of the Protestants, that they practice all acts of the Roman Catholic Religion as privately as possible, and that they remain silent during public discourses about Religion. (15) In fact, in the early years of the Maryland colony the only prosecutions for religious offenses involved Catholics who had interfered with Protestants concerning their religion. As a pragmatic realist, Calvert understood that he had to be tolerant about religion in order for his colony, which was never Catholic in its majority, to be successful. It was this conciliatory and compromising attitude the Calverts transplanted to colonial Maryland in the New World. Further, the Calverts put into practice that separation of Church and State about which other English Catholics had only theorized. Catholicism in New York Neither the Dutch nor English were pleased when the Duke of York converted to Roman Catholicism in 1672. His appointment of Irish-born Catholic Colonel Thomas Dongan as governor of the colony of New York was followed by the passage of a charter of liberties and privileges for Catholics. But the two-edged sword of Dutch/ English prejudice against the "Romanists" would soon re-emerge from the scabbard in which it had briefly rested.

That very fact made all the more incongruous the severity of measures that continued to be taken against Catholics, which included the draconian law of 1700 prescribing perpetual imprisonment of Jesuits and “popish” messengers. This strong anti-Catholic prejudice persisted even into the federal period. When New York framed its constitution in 1777, it allowed toleration for all religions, but Catholics were denied full citizenship. This law was not repealed until 1806. (18) The myth of religious toleration of Catholics in New York relies concretely, therefore, on that brief 16-year period from 1672 to 1688 when a Catholic was governor of the colony. Catholicism in Pennsylvania Due to the broad tolerance that informed William Penn's Quaker settlements, the story of Catholics in Pennsylvania is the most positive of any of the original 13 colonies. William Penn's stance on religious toleration provided a measured freedom to Catholics in Pennsylvania. The 1701 framework of government, under which Pennsylvania would be governed until the Revolution, included a declaration of liberty of conscience to all who believed in God. Yet a contradiction between Penn's advocacy of liberty of conscience and his growing concern about the growth of one religion – Roman Catholicism – eventually bore sad fruit.

Despite the more restrictive government imposed by Penn after 1700, Catholics were attracted to Pennsylvania, especially after the penal age began in neighboring Maryland. Nonetheless, the Catholic immigrants to Pennsylvania were relatively few in number compared to the Protestants emigrating from the German Palatinate and Northern Ireland. A census taken in 1757 placed the total number of Catholics in Pennsylvania at 1,365. In a colony estimated to have between 200,000 and 300,000 inhabitants, the opposition against the few Catholics living among the Pennsylvania colonists is testimony to an historic prejudice, to say the least. (20) Even in face of incessant rumors and several crises (e.g. the so-called “popish plot” of 1756), no extreme measures were taken and no laws were enacted against Catholics. A good measure of the prosperity of the Church in 1763 could be attributed to the Jesuit farms located at St. Paul's Mission in Goshehoppen (500 acres) and Saint Francis Regis Mission at Conewago (120 acres), which contributed substantially to the support of the missionary undertakings of the Church. (21) The history of the Jesuits has been called that of the nascent Catholic Church in the colonies, since no other organized body of Catholic clergy, secular or regular, appeared on the ground till more than a decade after the Revolution. (22) Relaxation of anti-Catholicism in the revolutionary era This phase of strong, blatant persecution of Catholicism came to a close during the revolutionary era (1763-1820). For various reasons, the outbreak of hostilities and the winning of independence forced Protestant Americans to at least officially temper their hostility toward Catholicism. With the relaxation of penal measures against them, Catholics breathed a great sigh of relief, a normal and legitimate reaction. However, instead of maintaining a Catholic behavior consistent with the purity of their Holy Faith, many of them adopted a practical way of life that effectively ignored or downplayed the points of Catholic doctrine which Protestantism attacked. They also closed their eyes to the evil of the Protestant heresy and its mentality. Such an attitude is explained by the natural desire to achieve social and economic success; it is, nonetheless a shameless attitude with regard to the glory of God and the doctrine that the Catholic Church is the only true religion. As this liberal Catholic attitude continued and intensified, it generated a kind of fellowship that developed among Catholics with Protestants as such. And so, an early brand of an experimental bad Ecumenism was established, where the doctrinal opposition between the two religions was undervalued and the emotional satisfaction of being accepted as Catholics in a predominantly Protestant society was overestimated. These psychological factors help to explain the first phase of the establishment among our Catholics ancestors of that heresy which Pope Leo XIII called Americanism. |

No comments:

Post a Comment